We’re surrounded by the fallout. Viral videos of grown women throwing tantrums. Stories from partners, children, and bullied women describing the emotional wreckage typical of Cluster B behaviour. You would expect this to be reflected in research, so why hasn’t the official prevalence of Cluster B been updated in two decades?

A look behind the official prevalence rate

The estimate often cited comes from the NESARC study by Grant et al. (2008), which puts BPD prevalence at 5.9%. But there are several reasons this likely underestimates the real number. The study used rigid DSM-IV checklists, ignoring people just below the threshold or those with intermittent symptoms that still cause major dysfunction. It also excluded overlapping symptoms with mood or substance issues, despite growing evidence that these overlaps are central to Cluster B. The interviews were done by laypeople, missing the nuance needed to spot patterns like relational chaos or emotional dysregulation. And they depended on lifetime recall which is hardly reliable in a group known for poor insight into their own behaviour. That would be like measuring a fever when you know the thermometer is broken. Lastly, the study reflects a pre-digital world, before online validation loops and a constant sense of danger.

Some studies and surveys do challenge the prevailing estimates. Jean Twenge’s reports on rising narcissism among college students are one such indicator. Another study found a measurable rise in certain traits over just five years, particularly among female students. But even this fails to capture the full range of the Cluster B condition, because they chose only to measure self-harm and alcohol abuse, deliberately leaving out common behavioural markers like tattoos, piercings, and impulsivity. It shows how easily psychiatric criteria bend with culture. Notably, this study shows how these behaviours can indeed intensify in response to social environments, not just innate predispositions. This isn’t a disorder people are born with; it develops.

So how do these traits develop?

These aren’t like other mental illnesses, that appear after an unpredictable or extraordinary events. They don’t necessarily require severe trauma or catastrophic abuse but may also take root quietly, in homes that look normal on the outside.

It develops already in adolescence, shaped by temperament, attachment patterns, and environment. At the core is often a lack of consistent emotional security through maternal care that is responsive and predictable, crucial for attachment and modelling soothing. Emotional security also depends on paternal involvement, which provides safety and helps develop impulse control through consistent boundaries and authority. Some children who grow up without this can experience feelings of rejection or abandonment, even in the absence of overt abuse or neglect.

Yet a sibling in the same household may not react the same way. The difference lies in personality. Individual variations that demand different kinds of parenting. Across species, variation in temperament (40–60% heritable) is the norm. In birds, high-predation environments produce more anxious offspring. Humans are no less responsive to early emotional climate, and this can explain the slow drift into maladaptive traits that define personality disorders.

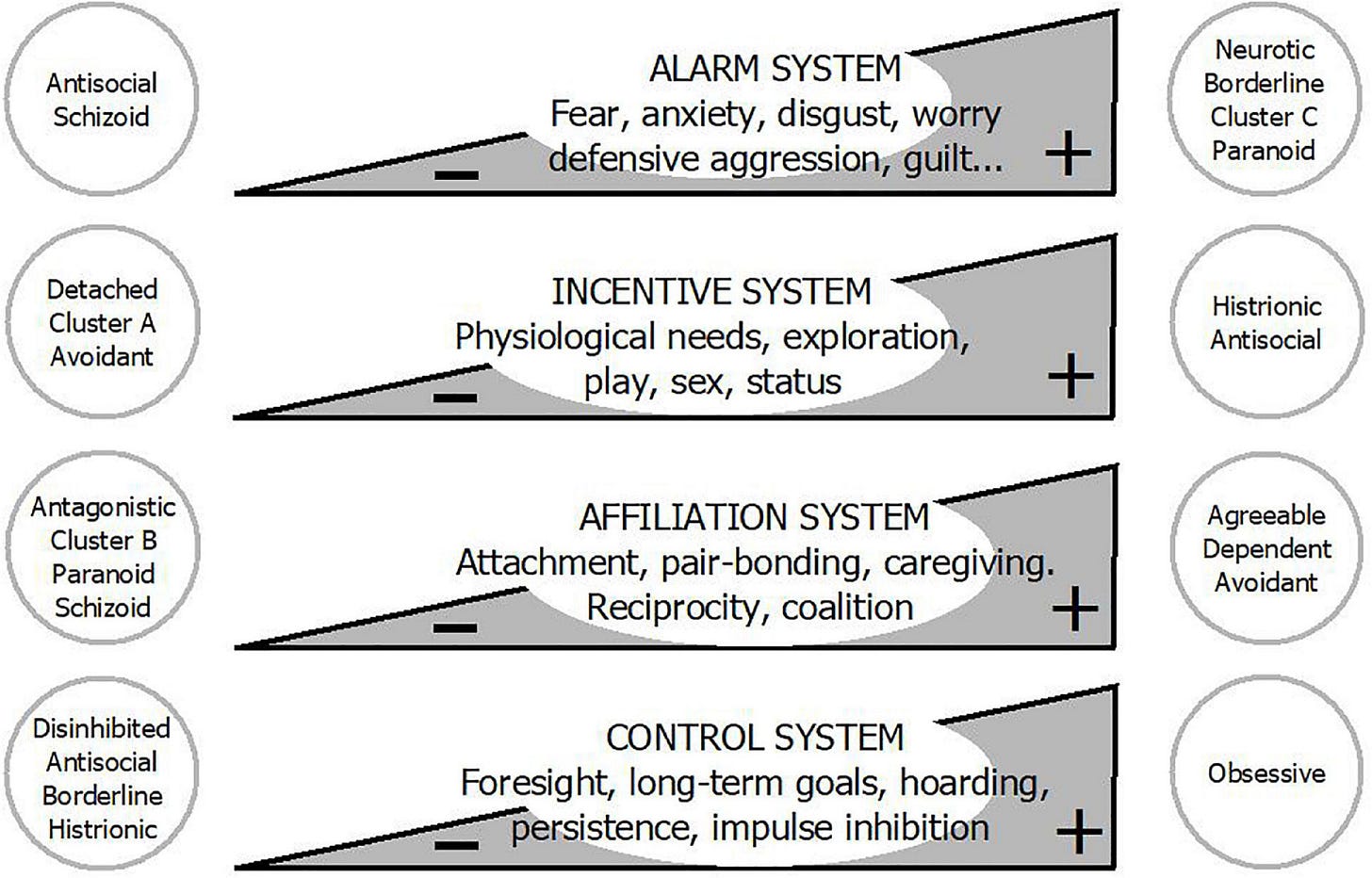

The most robust framework we have for understanding personality, the Five-Factor Model, describes traits along five dimensions: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness. But beneath these traits lie the deeper systems that drive them: alarm (threat detection), incentive (reward-seeking), affiliation (bonding), and control (regulation). These are evolutionary action systems that tell us when to flee, fight, attach, or take risks. Guiding us towards reproduction and survival.

What we call a personality disorder is often one or more of these systems thrown into overdrive or left underdeveloped. Cluster B traits, for example, often reflect a hyperactive alarm system (hypersensitive to threat), an underactive affiliation system (attachment insecurity), and a weak control system (impulsivity). Many learn, usually in childhood, that only through extreme emotional displays will someone attend to them. And any attention feels safer than being ignored.

But when does this become pathology?

While an excess of certain personality traits can be understood as an adaptation to one’s environment, rooted in inborn motivations and drives, the strategies that emerge from these traits often become maladaptive. Since psychiatry defines disorder in terms of impaired functioning, these traits are classified as pathological when they begin to interfere with work, relationships, or daily life. To meet the criteria for a personality disorder, dysfunction must touch nearly all domains: family, friendships, career, and leisure.

You can imagine how vulnerable this kind of diagnosis is to the bias of the observer and their assumptions about what ought to count as functional. And these assumptions shape not only clinical judgment but also research methodology. Take again the case of tattoos. Once viewed as a marker of impulsivity, they are now considered expressions of personal style. The threshold for what qualifies as dysfunction moves with culture.

Decades ago, visible tattoos could limit employment and were flagged in personality assessments as signs of social deviance or at least an inability to plan long-term. Today, they’re so normalized that they're no longer seen as clinically relevant, despite still serving the same psychological function.

Let me illustrate what that looks like in real life.

Take the 19-year-old girl I once had regular sessions with for over a year, diagnosed with BPD. She was trying to complete an apprenticeship in a preschool while living with her parents, whom she loved and hated in equal measure. The family was well off, living in a large house with her older sister and younger brother. She spent most of her free time, and much of the time she skipped work, with unsavoury characters and boyfriends her parents disapproved of.

She struggled with depressed moods and constant fatigue, had difficulty getting out of bed in the morning, falling asleep at night, and maintaining any kind of routine. This made it hard to meet the demands of the apprenticeship, which was already her third attempt.

One session, she walked in with a pained expression. I braced myself, sensing something worse than usual had happened. I feared she had been fired again, despite all the letters we had written to secure this final opportunity. She sat gingerly on the edge of the seat and said, “It happened again.”

“What happened again?” I asked.

“My mom went on one of her narcissistic tirades. She only wants me in the house to be her slave!”

I asked her to walk me through what had happened. In her version, her mother had expectations about helping around the house that she could never meet. No matter how well she cleaned or tidied, it was never good enough. A fight had broken out over how they had disappointed each other through the years.

“My mother is a prude and a bore and she’s jealous of my looks and my life. Why else would Dad never come to her defense? It’s because he silently agrees with me. I don’t even understand what he’s doing with her. I have to get out of that house.”

“It sounds like a difficult fight, where a lot of old wounds were reopened. That must have been upsetting. How did it end and what did you do afterward?” I asked.

“I just left. I had plans. I went to meet my boyfriend. We had tickets to a festival and I stayed at his place.”

At this point she flinched. I said, “It looks like you’re uncomfortable. May I ask if you hurt yourself?”

“No, it’s nothing. I just started on this tattoo.”

“May I see it?” I asked.

She lifted her shirt to reveal a large animal’s head inked on the side of her back.

“I needed to process,” she said matter-of-factly.

She saw this as a healthier response than cutting herself, which she had done in the past. To her, this was progress. It served several purposes. It was identity forming, it distracted from the emotional pain, and it felt like taking a stand as an adult.

Although it had been a couple of years since the last time she cut herself, was she not still harming herself? She had always been cautious with alcohol, never enjoying the feeling of being drunk. However, she would often smoke weed with her friends. But had she been part of a prevalence study, she wouldn’t have been counted.

Worse still, had she participated in the landmark longitudinal study that declared that BPD symptoms “remit” in 99% of cases over two years, she would have been deemed in remission. Since remission, in that study, was defined as reduced mood instability and self-harm, not improved work functioning, relationships, or life direction. She soon abandoned the apprenticeship and applied for lifelong reduced-ability benefits. So much for remission.

And sometimes the diagnosis is erased altogether.

Some argue that the label is sexist: a moral indictment of female behaviour. And in a bloated diagnostic system with significant symptom overlap, it’s easy to avoid the Cluster B category if you’re ideologically inclined to look the other way.

Consider the case of a 25-year-old Cluster B patient I’d been treating for over a year. When I returned to work after my honeymoon, she had been institutionalized during my absence. I phoned the university psychiatric hospital in question to inform them I was back and to coordinate preparations for discharge.

I was shocked to discover that after only two weeks, and just three sessions with the psychologist I spoke to on the phone, the diagnosis I had carefully established through extensive work up and regular sessions had been removed from the record and replaced with Bipolar Affective Disorder. Trying to stay calm, I asked how this had come about and how exactly the criteria were fulfilled.

The psychologist, rather arrogant and clearly annoyed, told me: “Her emotional instability can be understood within the framework of bipolar disorder, which I feel is a less limiting diagnosis, and frequently confused with borderline personality disorder.” She had, after all, spent 3 whole hours spread over 2 weeks with the patient, who had filled out questionnaires and reported episodes of elated, energetic mood followed by low mood and fatigue. The episode that led to hospitalization was, according to her, a classic depressive episode, not uncommon to include parasuicidal behaviour (in this case an overdose of sedatives).

With the full backing of the university hospital stamp, her diagnosis would take precedence. My attempts to give several concrete, firsthand examples confirming the validity of a personality disorder fell on deaf, impatient ears.

By the time the patient returned to me, she was convinced she had bipolar disorder and needed lithium. It took weeks to undo the damage. How many others elude the diagnosis entirely because of clinicians’ discomfort or ideological commitments?

Because the truth is, we no longer agree on what dysfunction even looks like.

If it’s perfectly normal to ditch family life, cut off relatives over election results, treat protesting like a full-time job, and throw tantrums because of oppression on Ivy League campuses, then what used to be called dysfunction is now just a lifestyle brand. Just like tattoos, the goalposts shift. This way, impaired functioning only counts when it’s extreme, and the prevalence rate remains unchanged.

This is where the ideological discomfort begins. If we take these traits seriously, not as fixed pathologies but as responses to instability, then we have to ask: what would help them settle? And the answer is deeply unfashionable.

What’s the antidote?

If we can understand what upregulates these behaviours, we can also understand what regulates them. I’ve observed that many of these traits begin to soften when patients build a life structured around stability, responsibility, and emotional attachment. Often to a reliable, emotionally stable partner.

Which would make sense given the expression of these traits is driven by a fearful environment, unreliable caregivers, and a constant sense of danger.

This is backed by the only treatment model we have robust evidence for: Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT), particularly its reparenting component. Through a stable therapeutic relationship, the therapist offers immediate and consistent responses—even outside office hours. The aim is to recreate, within the therapeutic frame, the attunement and reliability the patient lacked growing up.

I’ve offered this kind of therapy to girls and seen it work. As they grew attached to me, they began to care about my opinion, and that gave me an opening. I could point out what wasn’t working and suggest better strategies. I praised them when they made progress. These small moments of reinforcement made a tremendous difference. But it all depended on the bond, and that’s why it’s bound to fail in therapy:

When I went away for that two-week honeymoon, although they were placed with substitute therapists, the secure base was gone. By the time I returned, two had been hospitalized. Therapists, inevitably leave. Be it to burnout, maternity, job changes, or relocation.

That’s why the real antidote is the very thing we’ve abandoned.

We’ve cast aside stable frameworks, where people are bound and stay together out of true connection, as outdated. And until we’re ready to confront how easy it is to fail a child in our atomized, hyper-individualistic, productivity-obsessed culture, and begin to reckon with the psychological cost of simply not showing up, we will continue to underestimate how many are affected.

Only then can we truly assess the cost of modern childhood: the environments we normalize, the pressures we impose, and the fathers we remove.

In an effort to deflect from this uncomfortable truth, a growing movement now advocates dispensing with the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder altogether. That will be the focus of the next instalment.

Yes. I've wondered about tattoos. I've heard girls say, "It hurts so good." That strikes me as not normal. I've privately thought it seems related to self harm.

The last two generations are a mess and they will make their own children worse. Someone needs to start telling them "no" when they are little so they can cope with adversity when they grow up, assuming they ever do. I have lived a long time and have found that the only time to cry is when someone is happy or someone dies.