Borders or Borderliners: The Psychopathology Behind the Angry Female Protestors

Examining the rising prevalence rate of Cluster B traits

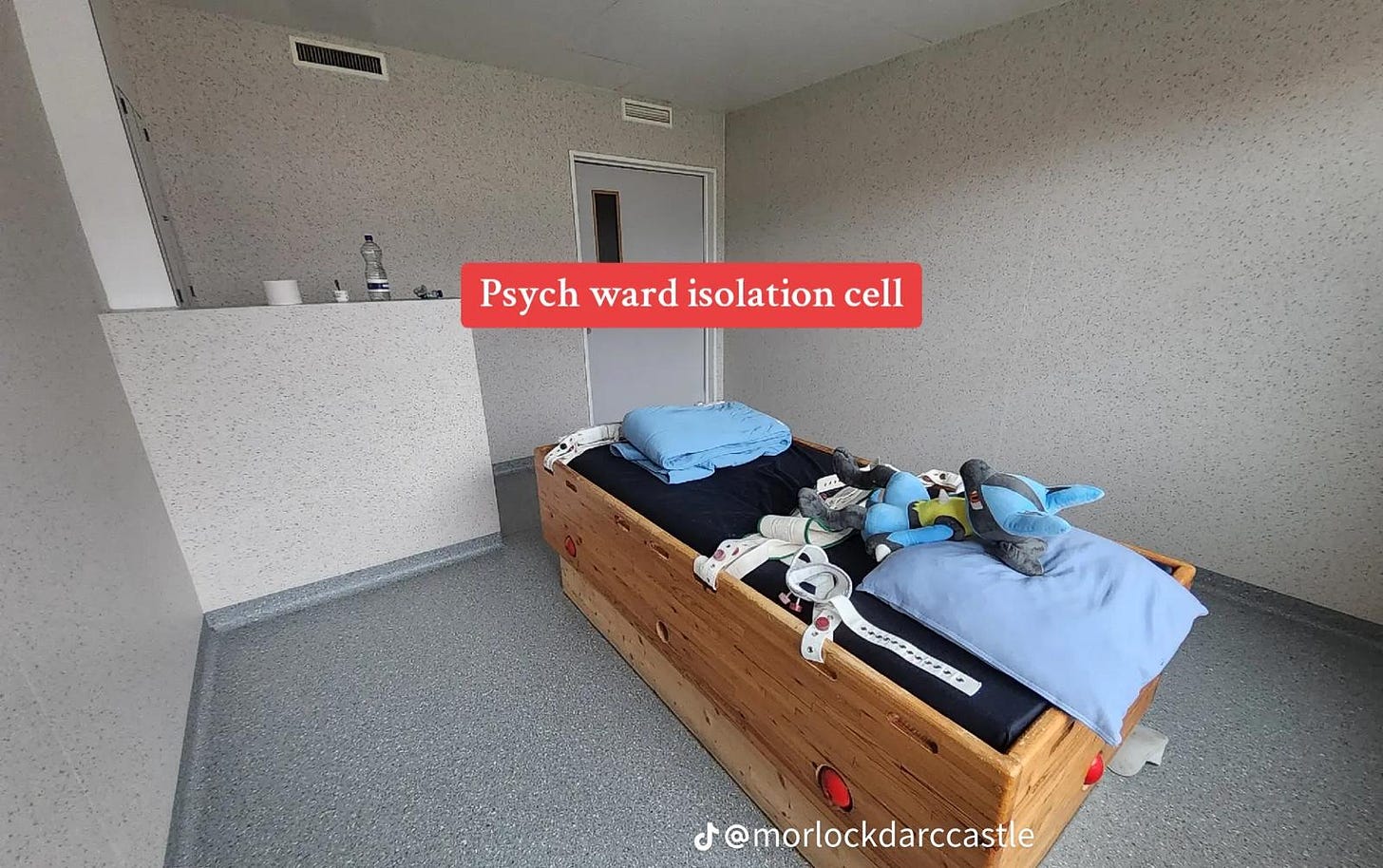

The Clinical Picture: A Case from the Ward

The walls were old and the rooms cold in the infamous Norwegian psychiatric hospital where I muddled through my first year of residency. Back then, I thought very differently about mental illness. I expected schizophrenia, mania, florid psychosis, but I found myself tangled in situations textbooks could never have prepared me for. It would be a long road before I shed the last layers of my naivete.

One of the first real lessons came on a weekend night shift. I was the only doctor on duty, hustling between buildings in the dark, juggling new intakes and the usual emergencies. That night, the emergency was a 23-year-old woman with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. She had cut herself deeply just below the elbow crease and I was called in to suture.

That was my emergency. Hers had already happened. A visit earlier that day that for some reason made her desperate to leave. When I walked into her room, the nurse greeted me with a brief nod, but the patient locked eyes with me immediately. There was no panic, just a calculated appraisal. She was working out what kind of doctor I was, and how she might get what she wanted.

No other doctors were on that weekend, so any discharge would have to come from me. Despite the tears and messy hair, despite the piercings and blood, she was striking—pretty, even—with a startlingly white smile she offered like a weapon. The contrast between her calm demeanour and the jagged wound was unnerving. But she seemed entirely unfazed.

I kept things light as I introduced myself and started prepping. I asked what had happened. She said she needed to go home because staying another night would push her over the edge. Never mind the improvement the nurse reminded her of having achieved over the three weeks prior. At home, she claimed, she had what she needed to calm herself, whereas in the hospital, no one cared.

She wanted me to protest, to reassure her that I cared and get pulled into the role of the rescuer. We doctors are easily baited that way.

While I tried to make sense of the incident, because I had to document it properly, she kept diverting. Asking about me and where I came from. The cutting, in her mind, wasn’t the issue. A reaction so instinctive it didn’t need explanation.

Eventually, I gave up trying to extract a coherent narrative and turned to the practical task. I drew up the lidocaine to numb the area. When she saw the syringe, she looked at me with sudden sharpness, a flicker of something fierce behind her eyes and a twitch in the lip “I don’t need that,” she said. “You can just stitch.”

“I have to numb it,” I replied. “The cut is long and in a sensitive area. You need to sit still, and with this much bleeding, it’ll take time.” “Doesn’t matter. Go ahead. I can take it.”

I froze. She was still bleeding. And time matters in wound care. But this wasn’t her first rodeo. She was daring me. I tried in vain to talk her into the anaesthetic, but she wouldn’t budge. The nurse gave me a shrug of resignation, not surprise. I couldn’t discharge someone who was a danger to herself, but she won the stand-off.

She didn’t make a sound through the entire procedure. I am no expert with a needle, and I know it must have hurt. But she watched calmly, dissociated. And I realized: they must have a different hierarchy of pain. Physical pain was familiar to her, perhaps even grounding. One she could control, in a life that that had honed dark, manipulative coping strategies, from wounds that ran much deeper than the one I was tasked with closing.

Later that evening, something happened that began to shape my understanding of this pathology. The same acute ward housed several other girls with Cluster B traits, and after that incident, one by one, they found ways to harm themselves. One broke a mirror in her bare room and used the shards to cut herself. I spent most of the night shift suturing.

That’s how borderline pathology spreads, through emotional contagion and group dynamics that feed dysregulation.

From Disorder to Social Norm

This girl’s self-harm was a learned method of coping with emotional chaos, one that had likely worked before to elicit being attended to. Her calm demeanour as I sutured the wound, her refusal of anaesthetic, her efforts to control my emotional response, all of it pointed to a deeper pattern. When internal suffering becomes unbearable and inexpressible, external injury becomes communication.

Her spiral had been triggered by a single emotional interaction earlier that day, showing how unstable her attachments were. Her belief that going home would fix everything, even though that same environment had recently led to crisis, revealed the black-and-white thinking, and lack of insight at the heart of this condition.

This story illustrates the core features of borderline personality disorder: emotional instability, impulsive behaviour, chaotic relationships, and a fragmented sense of self. It’s one of four disorders that fall under the Cluster B category, alongside narcissistic, histrionic, and antisocial personality disorders. These conditions share a common thread: erratic, emotionally charged, and often manipulative behaviour. While most of the cases I refer to involve borderline traits, the boundaries between these disorders are porous. Patients rarely present with traits from just one. That’s why I use the broader term—Cluster B.

While psychiatry is quick to diagnose high-functioning individuals with mental health disorders, it remains reluctant to recognize Cluster B conditions when they present outside the dramatic forms like the one I described above . But that’s only the visible tip of something much larger. Ideology clouds the root of the dysfunction and prevents us from discovering its true prevalence. As a result, countless individuals suffering from Cluster B traits, and inflicting harm through them, go undetected.

The Cost of Not Naming It

I focus on female presentations here because the least recognized Cluster B disorders, Borderline and Histrionic, are more commonly found in women. Antisocial personality disorder, the one Cluster B diagnosis more prevalent in men, often manifests as overt aggression, making it widely recognized, heavily studied, and frequently prosecuted. But the female-coded forms: manipulation, emotional volatility, and inward-directed harm as well as the way women express narcissism are far more likely to be excused, misinterpreted, or framed as trauma responses.

Evolutionary psychologists have established that females tend to cloak their aggression because they are vulnerable and need to preserve social cohesion for their survival. Thus, it takes subtler forms, like expressing moral outrage, often tied to progressive causes, and cloaked in the language of justice and compassion. On university campuses, we see borderline and histrionic traits play out in protests marked by rapid emotional shifts: from tearful victimhood decrying climate change to righteous fury chanting “from river to the sea, intifada revolution” without knowing neither the river nor the sea in question.

These movements, largely female, are often plagued by unstable group dynamics: intense but short-lived alliances and frequent infighting, reflecting the emotional volatility, identity instability, and heightened need for attachment characteristic of Cluster B disorders.

Narcissistic traits emerge in the way participants present themselves as moral authorities on complex geopolitical issues and women’s oppression in the West while showing little empathy and interest for the treatment of women or homosexuals in the regimes they defend. This is how females can cloak their aggression while exhibiting grandiosity, lack of empathy, and entitlement.

Histrionic traits are on full display in the TikTok mental health sphere. Users stage exaggerated emotional breakdowns, perform interpretive dances meant to convey distress, and employ seductive, attention-seeking behavior to draw views. One example: Natalie Reynolds manipulated a homeless woman into jumping into a lake for content. When banned from TikTok, she appeared at the company’s headquarters with a tearful, camera-ready plea demanding reinstatement. Her actions reveal hallmark Cluster B patterns: manipulativeness, lack of remorse, entitlement, and a need for admiration, all while refusing accountability.

Social media is saturated with self-harm symbolism: Public self-flagellation in the form of ally-guilt and narcissistic virtue signalling. Vindictive cancel campaigns showcasing narcissistic rage and intolerance of dissent. Deplatforming rather than debating is another form of subtle relational aggression.

The consequences are everywhere: rising workplace bullying in female-dominated sectors like HR, healthcare, and education. Infantilization in these spaces is often driven by childless women projecting unmet maternal instincts onto students, patients, and coworkers. What follows is maternal-style censure: punishment for disobedience and failing to align with the “right” causes, such as objecting to displaying the rainbow flag.

Because these behaviours align with female-coded forms of dysfunction, psychiatry hesitates to name them. To do so would risk sounding judgmental. As a result, they remain unrecognized as pathological, and the official prevalence rate of 5.9% has gone unchanged for over two decades. In the next instalment, we’ll examine why this number hasn’t been updated and answer uncomfortable questions about the nature personality disorders and the deeper forces driving their development.

Solzhenitsyn gave an excellent description of splitting with “the line that separates good and evil does not run between political parties, but right down the middle of every human heart.”

You are right that leftist women are morally primitive.

The psychiatric establishment’s silence on it is just (yet another) abdication of its rich clinical tradition.

Having been the spouse of a borderline I can attest to the damages caused.

It is very interesting to attribute at least some of the life we see playing out before our eyes as part and parcel of a more broad societal impact of this disease.

Fascinating